Taha Hussein

Remember You Doyen

Taha Hussein was born on October 28, 1898, in AI-Minya province, Upper Egypt, and grew up, the seventh of thirteen children, in a lower middle-class family. At a very early age, he contracted a simple eye infection and, due to faulty treatment by an unskilled local practitioner, was blinded, which caused him great anguish throughout his life.

He was placed in a kuttab (a school where children learn Quran and reading and writing) and was later sent to Al-Azhar University, where he acquired a thorough knowledge of religion and Arabic literature in the traditional manner. He felt deep discontent with the narrow thinking and conservatism of his tutors.

University Education

In 1908, he learned of the founding of a new, secular university as part of a national effort to promote education in Egypt under British occupation, and was very keen to enter it. He was blind and poor,but overcoming many obstacles, he was accepted in that university. He later stated, in AI-Ayyam (The Days) that the doors of knowledge were from that day opened wide for him. He was the first graduate of this university to receive a Ph.D. with his thesis on the skeptic poet and philosopher Abu-Alalaa’AI-Ma'arri.

Meeting Suzanne

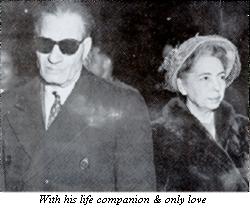

Again with much trouble, he was sent to study in France on the university's educational mission. His blindness caused him continuing pains, aggravated by a careless brother, presumably sent to take care of him. It was in France that he met his ‘sweet voice’, Suzanne, who came to read to him since not all the references needed were available in braille. She later became his wife, his mentor, advisor, assistant, mother to his children, great love and best friend. He states that since he first heard that 'sweet voice', anguish never entered his heart." After his death, she wrote Ma'ak (With You), published in Arabic; a touching remembrance of their life together.

Sorbonne Ph.D.

Taha Hussein specialized in literature and classical studies and was, again, the first Egyptian, and the only member of the mission, to succeed in obtaining first his B.A. from Montpellier University, and then his Ph.D. from the Sorbonne. His doctoral dissertation, written in 1917, was on lbn Khaldun, the fourteenth century Arab historian, the founder of sociology.

Through his own will and craving for knowledge, he grew to be the leader of the Arab cultural renaissance.

Advocate of Liberal Thought

His quest was to revive and sustain Islamic and Arab culture and language while espousing a western mode of thought. He became an advocate of liberal thought and translated many valuable works. Before Taha Hussein, the Classical Arabic language, was stagnant and heavily clicheed, and not in the reach of the general populace. His own style was quite easy to comprehend, yet it adhered to the rules of the language and fully exploited expressions and vocabulary. He urged for a cornrnon language to sustain Arab unity. Otherwise, he argued, the Arab nations would suffer the same problems of isolation suffered in Europe due to the language barriers.

Education for All

Taha Hussein strongly believed in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, in Arab unity, and in social reform. He fought fiercely for free education in Egypt, insisting, that "knowledge is like water and air," the natural right of every human being, and he made this his condition for accepting the post of Minister of Education in 1950. The new government, subsequently, declared ex-gratia primary education, a policy that remains in effect to this day. Millions of Egyptians owe their literacy to Taha Hussein.

His daughter, Amina, was among the first Egyptian women to graduate from university. She and her brother Moenis, later, translated his novel Adib (The Intellectual) into French. This is a deeply sympathetic story describing the cultural shock suffered by an Egyptian in the years he spent in France.

Constant Struggle

Taha Hussein lived a life of constant struggles - political, social and personal. After his death, his biography was completed by his son-in-law, Mohamed El Zayyat, in a book entitled Maba'd AI-Ayyam (Beyond the Days).

Three Kinds

Taha Hussein's works can be divided into three categories: scientific study of Arabic literature and Islamic history; creative literary works with social content combating poverty & ignorance, and political articles. The latter he published in the two papers of which he was editor-in-chief, after being expelled from his post as professor of Classical Arabic literature at the Egyptian University. His expulsion came as a result of public reaction to his book 'On Pre-lslamic Poetry', published in 1926, which gave full expression to his modern method of literary cirticism.

His Novels

His novels express an astounding sensitivity, insight and compassion in that age for a person with his background. His arguments for justice and equality are supported by deep and honest understanding of Islam. Equally remarkable are his sympathy with his downtrodden compatriots and his understanding of the deepest emotions and thoughts of woman as girl, lover, wife and mother.

Doyen

Taha Hussein, who had to bear the brunt of conservative attacks and confront enemies of his reforms, enjoyed affection of his pupils & colleagues. During his life time, he was elected member of many educational academies in Arab countries, and was honored by many international institutions. The American University in Cairo paid no heed to Egyptian Premier Isma'il Sidqi, when he warned against offering employment to Taha Hussein. Its Ewart Hall, where AUC holds its extra-curricular activities, was teeming in the 1930s with listeners eager to hear him and to declare him Doyen of Arabic Literature.

He was awarded honorary doctorates from French, British, Spanish and Italian universities. President Gamal Abd AI-Naser bestowed on him the highest Egyptian decoration, normally, reserved for heads of state. In 1973, he received the United Nations Human Rights Award.

Taha Husein died in October 1973, immediately after witnessing his country's victory in its last war against Israel. He died in his home, alone with his "sweet voice"; Suzanne.

She wrote: "We were together, alone, close to an extent beyond description. I was not crying - the tears came later. Each of us was before the other; unknown & united as we had been at the beginning of our journey. In this last unity, in the midst of this very close familiarity, I talked to him, kissing that forehead that was so noble and handsome, on which age and pain had not succeeded to carve any wrinkles, and no adversity had managed to cause to frown - a forehead that still emanated light".

"For before anything, and after everything, and above all things, he was my best friend, and he was, my only friend".

Exerpts from his writings:

"To those burning with their yearning for justice".

"To those rendered sleepless by their fear of injustice".

"To those and those together, I direct these words".

"To those who have what they do not spend".

"And to those who do not have anything to spend".

"Are these words directed".

He also wrote:

"I cannot find a more means of depicting Egypt during the later years of the monarchy than these two dedications". "He who belonged to the majority was unable to secure the means of his livelihood and the livelihood of those whom he supported. Thus he suffered his own deprivation and underwent the greatest and most hateful anguish in seeing the deprivation endured by his children".

"His eye was capable of coveting objects at the farthest reaches of sight, yet his hand had no reach at all. He would see delicacies at arm's length, and his heart would long for them and the hearts of his sons and daughters would long for them. Yet, when he attempted to grasp them, his hands would refuse to stretch out, as though paralysed, or as though bound to his body by the heaviest of chains".

"He would suppress his frustration and bid himself be patient with what he hated and bid his family be patient in the face of suffering and adversity, and he would await justice - but justice was very tardy in answering his call.

"He saw many blights attacking his body and spirit, and the bodies and spirits of his children. He would resolve to remedy their damage, but his ordeal would confine him and weaken his determination and he would be obliged to surrender himself and his family to these blights to work their will".

"He had resigned himself to ignorance, since his father had not been able to educate him. He strove to extract his children from the ignorance to which he had been confined, but could not find the means to do so. Thus, he accepted ignorance for his children as he had accepted it for himself, and he awaited justice that would allow them some of the enlightenment he had been denied in his youth. But justice slackened too long and was very tardy in answering his call and his children's call".

"He found wretchedness his detestable companion. It accompanied him when he set forth, and remained with him when he went home. It lived with him and his family in their home, if he and his family were allowed a home in which to find shelter".

"He would bid himself be patient with that detestable companion and he would bid his family be patient, certain that he was incapable of escaping it since he could neither hide underground nor flee to heaven. He awaited justice, which would rid him and his family of this despised companion. But justice was very slow to answer his call".

"Wretchedness would only accompany this majority along with its friends: hunger, nakedness, sickness, humiliation, degradation, toil that consumes and is never exhausted, and anxiety that intensifies and never relents. The people felt the greatest hatred for these companions and were most weary of them. But they found no means of ridding themselves of such burdensome fellows, unless justice should come and drop a veil between them. But justice was excessively tardy in coming, as though walking in chains; hardly taking a few steps when some force would pull it back to its resting place, where it remained, as far as it could possibly be from those who loved it and whom it loved, who pined for it and for whom it yearned."

He also serialized during the later years of monarch.

"Governments, willingly or unwillingly strove to please the prosperous. Perhaps some government members attempted to steal some reforms, looking upon the wretched of the earth with some compassion and endeavoring to touch them with a wing of mercy. But hardly would they start to do so, than they would find the earth quaking beneath them and find themselves isolated and bombarded by lecture after lecture, commanding them to comprehend that the aim of government was to increase the prosperity of the affluent and intensify the destitution and suffering of the wretched."

The government then in power took no heed of those words and paid them no attention. But one day they were assembled into a book, so that they might reach the hands of all readers and counsel the spendthrift, enlighten the privileged, and console the deprived. Thus was this book confiscated, among others that were meant to enlighten Egyptians with the reality of their affairs; advising the tyrants and oppressors, and relieving the wretched and desperate.

His type of literature

His type of literature became an independent form and readers competed in it passionately, reading and interpreting, discussing analyses, and extracting clear meanings from ambiguous allusions ... Looking at his publications, one will find allusions to phenomena that one abhorred and could not speak of openly during those dismal days. We preferred ambiguity to clarity, symbols and riddles to declaration, allusion and insinuation to calling things by their names.

The government of that era and its controllers would read and not understand. Thus, he defeated the oppression of tyrants and escaped the censorship of censors and manage to record the injustices of the unjust and the corruption of corruptors.